Cocktail Kafkaïne

Mustapha Benfodil / Joe Ford (translator)

cover artwork: Paul Hawkins

design & layout: Bob Modem

Mustapha Benfodil / Joe Ford (translator)

cover artwork: Paul Hawkins

design & layout: Bob Modem

Mustapha’s mixed-media installation Maportaliche / It Has No Importance at the 2011 Sharjah Art Bienniale was censored and removed. You can read more about it ︎︎︎here

Read Mustapha's The Last Six Days of Baghdad in Words Without Borders ︎︎︎here

Mustapha Benfodil was born in 1968 in Relizane, in western Algeria. He is a novelist and playwright, and works as a reporter at the Algerian daily newspaper El Watan. His books include Zarta (Editions Barzakh, 2000), Les Bavardages du Seul (Barzakh, 2003; prize for the best novel at the first Algerian Festival of the Novel, 2004), and Archéologie du chaos [amoureux] (Barzakh, 2007; published in France by Al Dante, 2012). He is also the author of five plays, including Clandestinopolis (2005; staged at the Avant-scène théâtre, Paris, 2008); De mon hublot utérin je te salue humanité et te dis blablabla (2009); Les Borgnes (2011); and End/Igné, his most recent piece. He published his reporting on the war in Iraq in Les Six derniers jours de Baghdad. Journal d’un voyage de guerre (Editions Casbah, 2003).

Joe Ford is a Teaching Fellow in Francophone Literature Durham University, and an Algerian Literature specialist. Joe was awarded his PhD in Francophone Algerian literature in July 2016. His thesis focused primarily on contemporary Algerian literature in French and what has become known as the Algerian Civil War of the 1990s. He has broad research and teaching interests in Francophone literature and visual culture from across North Africa, postcolonial studies, world literature, literary translation, and French and Francophone intellectuals of the 20th century. He is currently adapting his PhD thesis into a book, provisionally entitled ‘Writing the Black Decade: Francophone Algerian Literature’s Contestatory Forms’. You can read more about Joe ︎︎︎here.

Author’s preface for Cocktail Kafkaïne, in French and translated into English by Joe Ford.

Kafka à Alger

Cocktail Kafkaïne n’est pas une boisson (ni chaude, ni froide). Vous n’y trouverez ni caféine ni cocaïne ni l’équivalent de l’exquise mescaline chère à Michaux pour l’aider à aiguiser ses sens et son imagination. Non, désolé, ceci n’a rien d’un philtre prodigieux qui vous aurait permis de mieux supporter le poids de l’existence. Au mieux, c’est un breuvage métaphorique mais sans aucun pouvoir particulier si ce n’est celui des mots.

Je dois également avertir mon ami lecteur que les mots qui composent ce recueil ont très peu à voir avec la prose de Franz Kafka. Toutefois, j’ai bon espoir que l’esprit y soit. A Alger, ma ville, l’épithète « kafkaïen » est couramment invoquée tant n’importe quelle situation peut virer à l’absurde. Au risible. Comme le fait que la police vous demande une «autorisation», pour pouvoir lire de simples poèmes ou un extrait d’une pièce dans un lieu public, comme si la poésie pouvait constituer une menace de trouble à l’ordre public ! C’est ce qui m’est personnellement arrivé, et pas qu’une seule fois. Pendant une certaine période, les flics (en uniforme ou en civil), étaient d’ailleurs devenus mon premier public. Alors que j’avais lancé un concept intitulé « Lectures sauvages » (comme grèves sauvages), je me faisais systématiquement interrompre (quand je n’étais pas tout bonnement appréhendé) dès que j’investissais un espace pour un happening, une performance ou juste une lecture improvisée. Excédé, un jour, alors que des policiers sur les dents m’avaient demandé mes papiers avec autorité, je leur ai simplement répondu : « Je suis un extraterrestre ». Ils l’ont très mal pris et m’ont embarqué menottes aux poings. Tiens ! La prochaine fois, je leur tendrai un de mes poèmes en guise de papiers d’identité (peut-être Déclaration de Patrimoine).

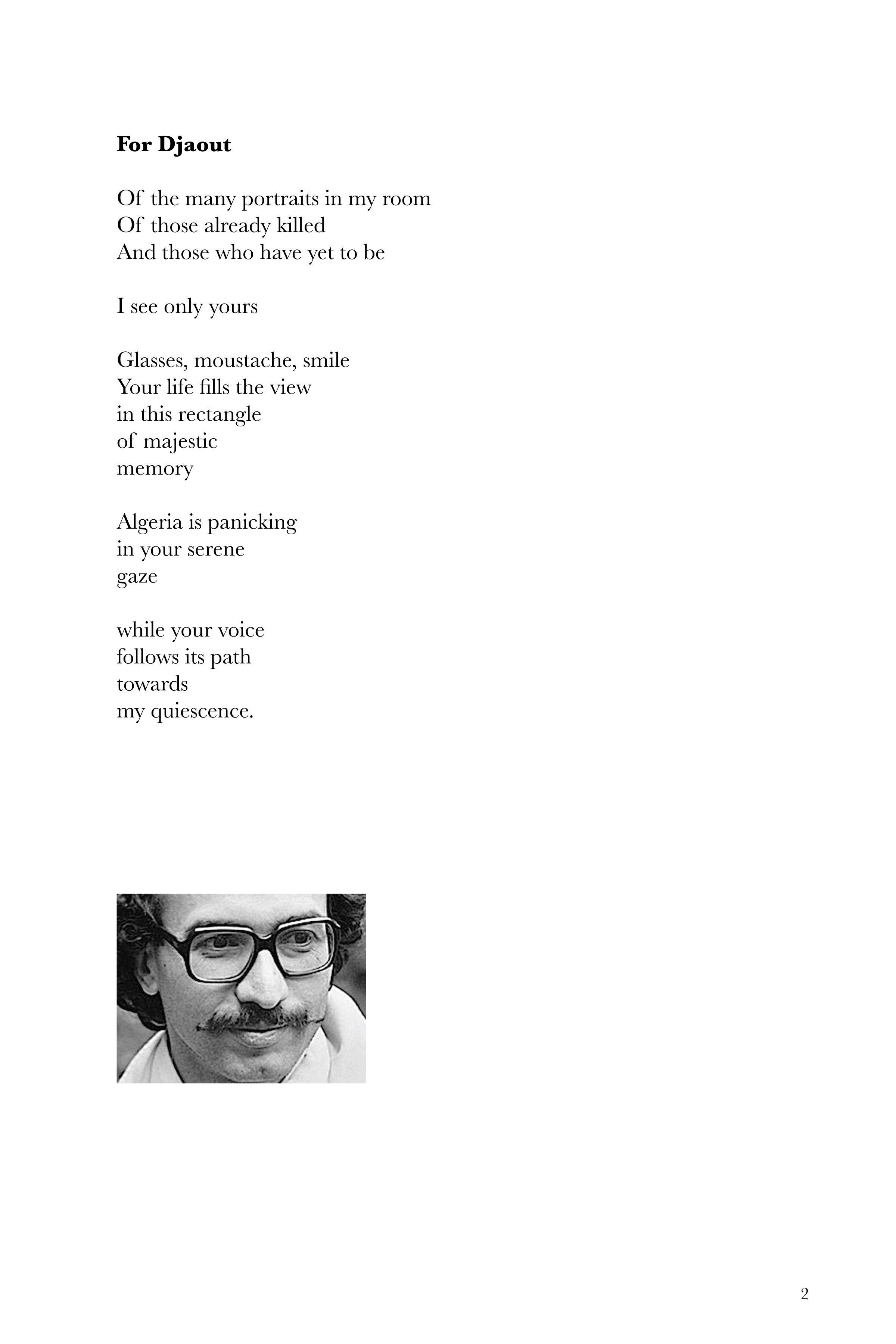

Ce florilège regroupe des textes éparpillés sur plus de vingt ans d’écriture. Celui qui ouvre cette anthologie, Pour Djaout, a été écrit peu après l’assassinat du poète et écrivain algérien Tahar Djaout le 26 mai 1993 près d’Alger. A l’origine intitulé « A la santé de la République », ce poème faisait 11 feuillets, mais malheureusement, j’ai perdu la version originale qui était dactylographiée, et je n’ai pu repêcher de ma mémoire que ces quelques lignes. Je dois avouer que même si j’ai été profondément marqué par ce qu’on a coutume d’appeler en Algérie « la Décennie noire », référence aux violences de masse des années 1990, je n’ai pas beaucoup de textes poétiques sur cette période. D’autres genres s’en sont chargés, spécialement mes romans.

Dans la diversité de leurs thèmes et de leurs formes, ces poèmes ont au moins deux points communs : leur résonance assumée avec le réel, et la liberté que je prends avec la langue. Pour moi, dire le monde de façon crue n’est pas antinomique avec le mot « poésie ». L’écriture poétique, dans mon esprit, c’est du rythme et des images. Les mots « poésie engagée », « poésie sociale », « poème-manifeste », « poète-militant »…ne me gênent pas. Dans l’idée que je me fais de la poésie, qu’elle soit classique ou contemporaine, lyrique ou expérimentale, il est important qu’elle tonne et résonne dans la cité jusqu’à faire trembler les piliers des temples, de la bourse et du palais. Car la poésie, pour moi, a quelque chose d’insurrectionnel. C’est une dissidence de la langue et une insurrection des sens contre l’ordre sémantique dominant. Contre le récit des dieux et le pouvoir narratif de ceux qui décident qui a voix au chapitre, qui délivrent les autorisations pour des lectures sages, dans une très belle…langue de bois. Mais heureusement, il y a l’autre poésie, la poésie/hérésie, celle qui, comme dit Camus de Kafka, nous offre « le luxe torturant de pêcher dans une baignoire, sachant qu’il n’en sortira rien ». [that poetry that, as Camus says of Kafka, offers us “the torturous luxury of fishing in the bath, knowing that there’s nothing there to catch”].

Kafka in Algiers

Cocktail Kafkaïne is not a (hot or cold) drink. You’ll find here neither caffeine nor cocaine, nor any other equivalent to the sumptuous mescaline so dear to Michaux, who used the drug to sharpen his senses and imagination. No, I’m afraid to say there is no prodigious potion that will help you better bear the weight of existence. At best, this is a metaphorical beverage with no particular power except that of words.

I must also warn my friend, the reader, that the words that make up this collection have very little relation to the prose of Frantz Kafka. Though, I hope that the spirit of his words is present. In my home town of Algiers, the epithet “Kafkaesque” is regularly invoked as any situation can quickly descend into the absurd. The laughable. Like the fact that the police can demand you obtain a “permit” to simply be able to read poems or an extract of a play in a public place, as if poetry constituted a threat to the maintaining of public order! And this is what has happened to me, on more than one occasion. For a certain period, my main audience were police officers (whether in uniform or plainclothes). When I founded the concept of “wild readings” (a bit like wild cat strikes), I was continually interrupted (if not placed under arrest) as soon as I took over a space for a spontaneous event, a performance, or simply an improvised reading. Exasperated on one such occasion, when police officers forcefully demanded to see my papers, I replied, quite simply: “I am an extra-terrestrial”. They took it very badly and carted me off in handcuffs. Hey! Next time I’ll give them one of my poems in lieu of my identity papers (perhaps Asset Declaration).

This collection brings together several texts written over a period of twenty years. The opening poem, For Djaout, was first written soon after the death of the Algerian poet and writer Tahar Djaout, murdered on the 26 May 1993 near to Algiers. Initially entitled, “To the Health of the Republic”, the poem was 11 pages in length, but I’ve since lost the original printed version of the poem and have only been able to recall the few lines reprinted here. I must admit, even I have been deeply affected by what we have come to call the “Black Decade” in Algeria (which refers to the mass violence of the 1990s), I have written very little poetry on this period. I have instead used other genres, especially my novels, to broach the Black Decade.

In their multiple themes and forms, these poems have at least two common features: their assumed resonance with the real, and the freedom in my use of language. For me, saying the world in a blunt or crude way is not in contradiction with the word “poetry”. In my mind, poetic writing is rhythm and images. I have no qualms with the designations “committed poetry”, “social poetry”, “poem-manifesto”, “militant-poet”. Whether classical or contemporary, lyrical or experimental, my idea of poetry is that it rails and resounds in the city space, shaking the pillars of temples, from the stock exchange to the palace. Because, for me, poetry has something of the insurrectional about it. It is a form of linguistic dissidence, an insurrection of the senses against the dominant semantic order – against the stories of the gods and the narrative power of those who decide who has a voice, against those who issue permits for the readings of wise men, composed in the most beautiful …demagogic tongue. But thankfully, there is the other poetry, a poetry/heresy, that which, as Camus says of Kafka, offers us “the torturous luxury of fishing in the bath, knowing that there’s nothing there to catch”.

Mustapha Benfodil / Joe Ford

Feb 2018

on Mustapha Benfodil & his work(s)

Nul besoin de paradis artificiel, de cocaïne, de bière ou de caféine. Dans son «maquis littéraire», Mustapha Benfodil se roule des joints avec les sons et les mots.

No need for drugs, cocaine, beer or caffeine. In his 'literary underworld', Mustapha Benfodil rolls joints with sounds and words.

- Sylvie Brodziak (Cergy-Pontoise University)

Mustapha Benfodil est un personnage inclassable, mi-public, mi-secret. Côté public, l'engagement pour les autres, l'empathie profonde pour les drames de l'histoire, ceux de la paysannerie algérienne (...), ceux des victimes du terrorisme ou des conflits qui déciment le monde arabe ; côté secret, le même engagement, mais dans l'écriture qu'il situe comme ‘écriture post-traumatique’. Mustapha Benfodil is an unclassifiable writer, half visible, half hidden from view. Visible is his commitment to others, his profound empathy in interpreting the dramas of history, from the Algerian peasantry (...), to the victims of terrorism or of conflicts that decimate the Arab world. Less visible is a parallel commitment to what he himself has named a 'post-traumatic writing'.

- Nadia Saou, El Watan newspaper

Benfodil étreint une génération qui a sa propre musique, ses propres idoles et ses fantasques onomatopées. Benfodil captures a generation that has its own music, idols and onomatopoeic whims. - Sid Ahmed Semiane aka SAS, writer / film-maker

Benfodil creates new artistic processes designed to renew the cultural field. The tangible materiality of this literature-action, I contend, serves an essential role in illustrating how Algerian francophone literature connects with its society and 'becomes' Algerian.

- Alexandra Gueydan-Turek (Swarthmore College)

Benfodil's writing is lyrical, immediate and unapologetic.

- Anthony Downey, www.ibraaz.org

Read a ︎︎︎review by Sally-Shakti Willow for The Contemporary Small Press

Cocktail Kafkaïne Book launches 2018

Mustapha & Joe read from Cocktail Kafkaïne. Readings & discussion were in English & French.

March 5: Empty Shop HQ, 35c Framwellgate Bridge, Durham DH1 4SJ starts 20:00

March 7th: Quaker Hall, Quaker Meeting House, 188 Woodhouse Lane, Leeds LS2 9DX – early reading 17:00